Enlightenment

Human Body

Human Mind

Human Spirit

Vision

| Untying | Body | Mind | Spirit | Vision |

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5

By designing a permaculture garden, we improve on industrial agriculture in many ways.

Each small area of land becomes a multi-storey field - a food forest.

By carefully mixing tall trees, short bushes, ground crops and root crops, we to produce far more food than we can in a single or dual crop field.

instead of allowing it to run off, or evaporate

- water shortage problems are resolved.

By choosing a wide variety of crops, we can have fresh foods available all year round,

with the entire garden being our refrigerator and health food store.

And for animal lovers, we encourage wild life as this is an integral part of nature,

and is constantly working for us.

Nature is far more efficient than anything man could ever devise,

and all we have to do is observe,

and adjust what we plant in accordance with what we see.

Permaculture gardens can be anything

from a small terrace in an apartment block to a lawn,

to a small plot of unused city land,

to a fully grown food forest.

One major benefit is that after initial design and construction,

there is no ploughing, digging, or weeding.

Maintenance takes only a few days per year, with the major work being harvesting.

Permaculture is not only a farming method, it is a philosophy,

and includes housing design, using natural materials.

Permanent agriculture - permanent culture.

The central resource for all things permaculture is

Permaculture Research Institute of Australia

An excellent resource, with Permaculture lessons is at:

http://tim-gamble.blogspot.com

Permaculture explained

Globally, since 1940, we have cleared forest areas the size of North America.It's amazing how much destruction we can create without thinking about what we are doing.

Since 1940, 70% of our soils have been destroyed.

40% of the water of the world has been poisoned by agriculture.

A species is lost every 6 minutes.

If we don't stop agriculture, then we are all dead.

Nothing is so destructive.

Action is necessary NOW

|

A Fukuoka

designed garden

Gardening in France using Fukuoka techniques |

|

Homegrown

Revolution

The

Dervaes live off their land

|

| Global

Gardner - Part One |

Global Gardner - Part Two | |

|

Global

Gardner - Part Three

|

Global Gardner - Part Four | |

|

Homegrown

- Trailer

|

Permaculture

Principles at work

|

Rise_of_the_Forest Gardeners

Natural Farming Greening the Deserts

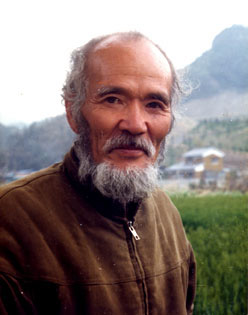

Japanese Farmer-Philosopher Fukuoka MasanobuBy Yoneda Yuriko

A farming method called 'natural farming' needs no tilling, no fertilizers, no pesticides, and no weeding. For about 60 years, Fukuoka Masanobu, Japan's renowned authority on natural farming, honed methods based on his unique theories, insights and philosophy. His seminal book, "One-Straw Revolution," first published in 1975, has been translated into English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Russian and other languages, and has been read around the world. The book addresses not only the practical aspects of natural farming but also the root causes of environmental deterioration. Fukuoka's thought and philosophy have inspired many people worldwide by pointing out a way of life. Here we introduce his thought and practices.

Fukuoka was born in 1913 in Iyo, Ehime Prefecture, in the southern island of Shikoku in Japan. After graduating from an agricultural high school, he took a job at the Yokohama Customs Office. At the age of 25, however, he was hospitalized with acute pneumonia. The days spent alone became a turning point in his life. After leaving the hospital, he continued to reflect on matters of life and death. One morning, a flash of insight came to him: "There is nothing in this world. No matter what humans try to do, they can achieve nothing. Every thought we have and every action we take is unnecessary." This was the birth of Fukuoka's philosophy, "the theory of the uselessness of human knowledge," or the theory of "mu" (nothingness).

To demonstrate his theories in practical ways, in 1937 he returned to his native village and become a farmer at his father's orange orchard. In 1939, when Japan's situation in World War II began to deteriorate, he started to work at an agricultural research station in Kochi Prefecture as an instructor and researcher on scientific farming, and continued there until the end of the war. He returned to Iyo in 1947, and continued to work on his unique natural farming system.

He visited America in 1979 and saw California's desertified land, it occurred to him that his natural farming method would work to green these regions. Visiting American communities working on natural farming, he kept telling people that modern large-scale farming and cattle-raising were causing desertification.

During one speaking tour, the head of the United Nations department in charge of combating desertification asked him for technical advice. This was the starting point of Fukuoka's initiative for desert greening all over the globe: in China, India, the Americas, and Africa. Farming Based on Spiritual Philosophy Fukuoka's natural farming method begins with the absolute rejection of science. He says in one of his books, "My study started with the rejection of conventional agricultural technologies. I absolutely reject science and technology. My view is based on the rejection of Western philosophy, which supports today's science and technology."

He continues, "Natural farming, in my mind is, in fact, not part of so-called scientific agriculture. I aim to establish a new farming method from the perspective of Eastern philosophy, thought, and religion, moving away from the framework of scientific agriculture." He values not the Western concept, that nature is for the use of humanity, but the Eastern way, that humans are part of nature. Through natural "do-nothing" farming he tries to demonstrate that science is imperfect and unnecessary. In another book, "The Road Back to Nature," Fukuoka notes, "Dietary abnormality results in abnormality of the body and mind, and affects everything. A sound body comes from healthy food. A sound idea comes from a healthy body." He considers food the most significant factor in human life, and he repeatedly uses the Daoist or Buddhist term "shindo-fuji" in his books, which literally means that body (shin) and earth (do) are inseparable (fuji). That is, humans and the environment are united. When people eat food in season, grown on the very land where they live, their bodies can be sound and in harmony with the environment. Currently, most farmers in Japan practice chemical farming using chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides. Recently, however, with people paying more and more attention to food safety, an increasing number of farmers practice sustainable agriculture, through reduction of herbicides and pesticides and/or through the use of organic fertilizers.

At supermarkets and retail stores, consumers are able to buy agricultural products bearing the Organic JAS (Japanese Agricultural Standard) logo, certifying that food has been produced in accordance with international guidelines. JAS certification is given to agricultural products from farms which have not used agrichemicals and chemical fertilizers for more than three years. Is Fukuoka's natural farming just one type of organic farming? Fukuoka rejects scientific farming based on human knowledge. Instead, he has established a farming method that requires as little human intervention as possible.

Organic farming, in which people spread organic fertilizers, is different from what he has been aspiring to prove. Fukuoka explains natural farming: "We can make healthy rice, healthy and rich soil that requires no fertilizer, and have productive soil without tilling if we just accept the fact that excessive efforts--tilling, application of either organic, chemical fertilizers, or pesticides-has never been necessary.

A farming method that develops the conditions under which people do not have to do anything--this is what I have been pursuing. After thirty years I finally came to the point where my natural farm could yield, without any effort, virtually as much rice and wheat as typical scientific farms."

Japan For Sustainability Newsletter interviewed Matsumoto Muneo, who has been attempting Fukuoka-style natural farming in Saitama Prefecture, in the suburbs of Tokyo. According to him, a few farmers are now practicing "natural farming" across Japan.

But there is no set definition of natural farming as each person approaches it in his own way. Having learned natural farming from Fukuoka, they have adapted it to their circumstances. Fukuoka's natural farming could be described as the prototype, or at least one of the sources of a stream. The principles of Fukuoka-style natural farming are no tilling (cultivation), no fertilizers, no pesticides, and no weeding. Although "no tilling" may be a difficult concept for ordinary farmers to understand, Matsumoto explains that "Tilled soil easily dries out." He continues that the application of fertilizers, including manure, overprotects plants. By contrast, plants without fertilizer can grow to be robust and tasty.

Regarding the principle of no weeding, he cuts weeds when they bloom, instead of pulling them out. And the mowed weeds, laid flat on the ground, keep soil moist in summer and warm in winter; eventually they decompose into natural fertilizer. Moreover, Matsumoto rarely waters the plants so that the roots search for water and stretch deep. If water is abundant, he says, plants will have shallow roots and become weak from getting water too easily. When seeding, Matsumoto scatters a mixture of seeds. A plant sprouts only when it best suits the place, and thus he cannot anticipate in advance what will grow where.

To those who do not know better, Fukuoka-style natural farms may appear to be untended, with plants growing randomly. Neighbors often despise such farms, thinking that they look disorderly. In this country, where most farms have vegetables growing in neat rows, natural farming may be hard to understand for most people. An agricultural method that requires no tilling, no fertilizers, no pesticides and no weeding sounds quite easy. But in reality it is not. In his books Fukuoka stressed repeatedly that the "natural" in natural farming is different from noninterference. Matsumoto elaborates: "Nature without human intervention just follows its course automatically. However, nature once tampered with by humans will not return easily to its original condition without human intervention."

Restoration of the original natural conditions is rather difficult to accomplish and certainly requires expertise. Fukuoka was able to establish his natural farming method only through repeated attempts and failures, eventually returning his own fields to the natural condition.

The rapidly growing demand for petroleum in recent years is giving rise to conflicts all over the world. In chemical-based agriculture, petroleum is not just the material used to make fertilizers and pesticides but also the fuel to power cultivation machinery.

In contrast, natural agriculture requires no cultivators, fertilizers or pesticides. Since it does not depend on petroleum, it is a more sustainable form of agriculture.

Greening of Deserts with Clay Balls

Fukuoka's natural rice farming method is a "no-tilling, direct sowing, rice-barley double cropping" system in which rice and barley grow in the same field alternately in a year, from seeds sown on non-tilled fields.

Knowing that bare seeds tend to be eaten by birds, Fukuoka came up with the idea of inserting seeds into clay pellets before sowing them on fields. In general, such clayballs are made by (1) mixing clay, water and various kinds of seeds, (2) removing air bubbles from the mixture as much as possible, (3) forming small, round balls, and (4) drying them for 3 or 4 days. Clay-coated seeds are prevented from being eaten by birds or insects and also from drying up. The globular shape of these clay pellets makes them hard to break. Clayballs contact the ground with a small area where dew is formed due to differences in daytime and nighttime temperatures, which facilitates the rooting of seeds. Clayballs are especially suited for sowing in deserts since they require no watering or fertilizers in addition to their low-cost nature.

Fukuoka launched a movement for desert-greening with clayballs, and succeeded in greening activities in Greece, India, Tanzania, the Philippines, and worldwide. Although Fukuoka is now retired from the movement, activities that he initiated continue in many countries. It takes years before the deserts can be transformed into green areas filled with germinating seeds, small plants, vegetables and trees. In other words, it is rather easy to destroy nature, but restoring nature once lost requires tremendous time and energy.

Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives

After World War II, Japan has expanded economically and become a country that imports materials from all over the world. Even the food, which is essential for our survival, comes from as far away as the other side of the planet. Through this change, Japan has achieved affluence. On the other hand, agriculture is now largely detached from the lives of most people in this highly technological society. Humanity cannot live without nature. The farmer-philosopher Fukuoka has shown us that natural agriculture allows us to live without the aid of technology. We should never forget that it is nature that sustains our lives. Scattering seeds to bring back nature and agriculture closer to our daily lives may be one step toward a sustainable society.

In 1988 Fukuoka received the Deshikottam Award, India's most prestigious award, and the Philippines' Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service, recognized as Asia's Nobel prize.

In 1997 he received the Earth Council Award, which honors politicians, businesspersons, scholars, and non-governmental organizations for their contributions to sustainable development.

Today, the 93-year-old Fukuoka has retired from the greening movement, and lives a quiet life in his home village, Iyo. His fields are now closed to the public.

Yoneda Yuriko is staff writer for Japan for Sustainability This article originally appeared in the Japan for Sustainability Newsletter #45, May 2006. This slightly abbreviated version of the article was published at Japan Focus on January 28, 2007.

Cuba has already experienced “peak oil” when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1990. How can a community survive and eventually thrive after a loss of 80 percent of its oil and fertilizer inputs? The answer is community interaction, urban organic agriculture, and land rights to small farmers. Today more than 50 percent of the vegetable needs of Havana’s 2.2 million people is supplied by local urban agriculture. There are over 1,000 kiosks in Havana selling locally grown food. In smaller cities and towns the rate is between 80 to 100 percent.

Farmers are now among the highest paid workers. When the “special period” began in the early 90s, every vacant lot in the city was turned into a farm or a orchard. People cleaned up the land and started growing food. They just did it by trial and error. In 1993 the first Australian permaculturists came to Cuba to start the first train-the-trainer course. Today over 400 permaculture instructors have been trained in Cuba.

This page is mirrored on Google sites, Angelfire, and Fortune City

| The BTI Group |

|||||

| Enlightenment on Googlesites | Enlightenment on Angelfire | Enlightenment on Fortune City | Twas Meant To Be Blog | Enlightening Books | The BTI Institute |

| Sunday Humour 1 | Sunday Humour 2 | Sunday Humour 3 | China Sunday | David’s Writing Lessons | Contact

us: dgwest7 at gmail.com |