Enlightenment

Untying

Page

2 - More on home food growing and permaculture

What is Permaculture?

Permaculture (permanent

agriculture) is the conscious design and maintenance

of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have

the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural

ecosystems. It is the harmonious integration of

landscape and people providing their food, energy,

shelter, and other material and non-material needs

in a sustainable way. Without permanent agriculture

there is no possibility of a stable social order.

Permaculture

design is a system of assembling conceptual,

material, and strategic components in a pattern

which functions to benefit life in all its forms.

The

philosophy behind permaculture is one of working

with, rather than against, nature; of protracted and

thoughtful observation rather than protracted and

thoughtless action; of looking at systems in all

their functions, rather than asking only one yield

of them; and allowing systems to demonstrate their

own evolutions.

Permaculture

in Landscape and Society

As

the basis of permaculture is beneficial design, it

can be added to all other ethical training and

skills, and has the potential of taking a place in

all human endeavors. In the broad landscape,

however, permaculture concentrates on

already-settled areas and agricultural lands. Almost

all of these need drastic rehabilitation and

re-thinking. One certain result of using our skills

to integrate food supply and settlement, to catch

water from our roof areas, and to place nearby a

zone of fuel forest which receives wastes and

supplies energy, will be to free most of the area of

the globe for the rehabilitation of natural systems.

These need never be looked upon as “of use to

people”, except in the very broad sense of global

health.

The

real difference between a cultivated (designed)

ecosystem, and a natural system is that the great

majority of species (and biomass) in the cultivated

ecology is intended for the use of humans or their

livestock. We are only a small part of the total

primeval or natural species assembly, and only a

small part of its yields are directly available to

us. But in our own gardens, almost every plant is

selected to provide or support some direct yield for

people. Household design relates principally to the

needs of people; it is thus human-centered

(anthropocentric).

This

is a valid aim for settlement design, but we also

need a nature-centered ethic for wilderness

conservation. We cannot, however, do much for nature

if we do not govern our greed, and if we do not

supply our needs from our existing settlements. If

we can achieve this aim, we can withdraw from much

of the agricultural landscape, and allow natural

systems to flourish.

Recycling

of nutrients and energy in nature is a function of

many species. In our gardens, it is our own

responsibility to return wastes (via compost or

mulch) to the soil and plants. We actively create

soil in our gardens, whereas in nature many other

species carry out that function. Around our homes we

can catch water for garden use, but we rely on

natural forested landscapes to provide the condenser

leaves and clouds to keep rivers running with clean

water, to maintain the global atmosphere, and to

lock up our gaseous pollutants. Thus, even

anthropocentric people would be well-advised to pay

close attention to, and to assist in, conservation

of existing forests and to assist in, the

conservation of all existing species and allow them

a place to live.

We

have abused the land and laid waste to systems we

never need have disturbed had we attended to our

home gardens and settlements. If we need to state a

set of ethics on natural systems, then let it be

thus:

-

Implacable and

uncompromising opposition to further disturbance

of any remaining natural forests, where most

species are still in balance;

-

Vigorous

rehabilitation of degraded and damaged natural

systems to stable states;

-

Establishment

of plant systems for our own use on the least

amount of land we can use for our existence; and

-

Establishment

of plant and animal refuges for rare or

threatened species.

Permaculture

as a design system deals primarily with the third

statement above, but all people who act responsibly

in fact subscribe to the first and second

statements. We believe we should use all the species

we need or can find in our own settlement designs,

providing they are not locally rampant and invasive.

It

has been nearly three years since my husband Kim and

I decided we wanted to find a piece of land

somewhere where we could raise most of our own food

and lead a healthier, more sustainable lifestyle. By

March of 2007, we were the proud new owners of a

beautiful farm just under 44 acres in North Central

Idaho.

Now

what?

We

knew we wanted to raise fruits and vegetables and

medicinal herbs without chemicals so organic farming

interested us. We also wanted to build a straw bale

house and raise our own livestock for meat, eggs and

dairy. We started researching different methods and

one day an article in Mother Earth News magazine

changed everything. The name of the article was,

“Plant an Edible Forest Garden” by Harvey Ursery.

The article started out by asking questions. “Are

you feeling adventurous?” Sure! “Do you want to

delve deeper into gardening?” Why, yes. Even better,

"are you thinking of planting an orchard?” Wow, this

guy must be psychic… how did he know? It went on,

"If so, consider planting a forest garden….”

Kim Pagliaro and Geoff Lawton

Discussing Our Design |

The

idea of working with nature and imitating natural

systems clicked with us. It made perfect sense. I

thought we had better find out more about this

Permaculture stuff! Within a short period of time, I

knew quite a bit about the history of Permaculture

and the credentials of Bill Mollison and Geoff

Lawton. I signed up for a Permaculture webinar

offered by Midwest Permaculture in the States and

shared what I had learned with my husband. The next

logical step was to take a Permaculture Design

Course, but which one and where? And then… I found

it… the Tagari website! Bill Mollison was still

teaching Permaculture and there was a PDC scheduled

in three months in Melbourne, Australia! I told Kim,

“Did you know Bill Mollison and Geoff Lawton are

teaching a PDC in Australia in January? It sure

would be fantastic to learn from one of the most

experienced teachers ever, not to mention the man

that started it all, wouldn’t it?” I think he

muttered back, “Yeah, sure…we’ve always wanted to go

to Australia”. At this point it was more of a joke

then a plan but I couldn’t resist checking the

airfare prices. We had saved some money to dig a

well on the farm, but perhaps this was more

important. To make a long story short, three months

later, my husband and I, and our daughter, Kelly,

found ourselves on a plane to Melbourne.

It

is no exaggeration that a Permaculture design

certificate course is a life changing experience.

While not all Permaculture students go on to teach,

we were sure before the end of our PDC, that

establishing a demonstration farm and educational

center on our farm in Idaho was what we wanted to do

with the rest of our lives. As an added bonus, our

then eleven-year-old daughter Kelly, who just came

along for the ride, ended up with a Permaculture

Design certification as well.

Immediately

after returning to Las Vegas from Melbourne, the

three of us planted a Permaculture garden using

raised beds We also set up a website (www.kamiahpermaculture.com)

and organized an Introduction to Permaculture class

the following month. We went on to host three

different Permaculture Film and Discussion events at

the Las Vegas Springs Preserve featuring Bill

Mollison’s The Global Gardener and Geoff Lawton’s

water harvesting and food forest videos. Last

August, we were lucky to have Geoff and Nadia Lawton

visit our farm to consult on our design and we held

a small meeting in the town of Kamiah to introduce

some like-minded members of the local community to

the Lawtons.

Setting up rainwater harvesting system

Returning

to our regular jobs seemed somewhat strange. Our

outlook on life had changed. I felt as if there was

something more important I should be doing. We knew

we would eventually make the move to Idaho full time

but the idea of leaving the security of a good

paying occupation was very terrifying. We continued

to prepare for our eventual relocation. We stopped

leasing our land to a cattle farmer, who has

obviously never heard of rotational grazing, and

attempted digging our first swale. Last fall, we set

up our rainwater harvesting system by installing

gutters on our barn roof (our only existing

structure which happily sits on the highest point on

our farm).

The

global economic situation put us at a crossroads. It

was time to choose…stay in our current situation of

a mainstream family always trying to make ends meet

and accumulate more stuff but never feeling

fulfilled and put our demonstration farm plans on

hold, or take the leap and have faith that by doing

something meaningful, things would fall into place

and everything would work out. Why couldn’t we have

thought of this when we were in our twenties? I have

to say this has been the biggest challenge our

family has ever faced… to make that decision to move

forward. We have decided to take the leap. To say we

are going to experience a lifestyle change is an

understatement. We purchased a yurt to live in until

we can build a straw bale house and started a small

sheet mulch garden. We do not have a well or

municipal source of water, only rainwater. Some

people think we are a little crazy.

Now

we are offering our first Permaculture classes at

our farm this summer with the help of experienced

Permaculture designers/teachers. In August, we are

offering a Permaculture Design Certificate course

with Jesse Lemieux of Pacific Permaculture, British

Columbia, Canada on August 23rd – September 4th,

followed by Water For Every Farm, a three-day

earthworks course, Sept. 5-7th, 2009, taught by

Warren Brush of Quail Springs Permaculture located

at Quail Springs in California.

We

are as excited about this change for our family as

we are scared but we are also optimistic.

Permaculture has given us hope for the future, our

future…everyone’s future. The world needs

Permaculture now. To share it with others has never

felt so right.

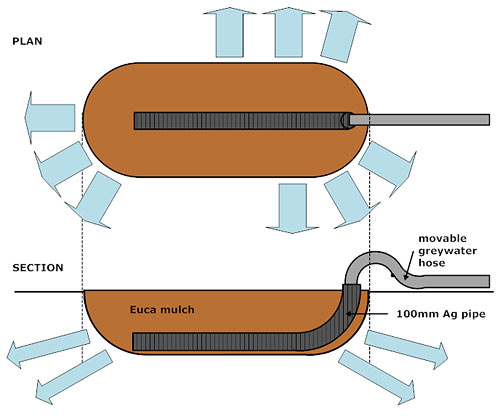

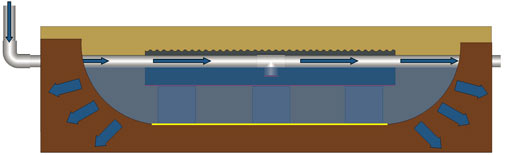

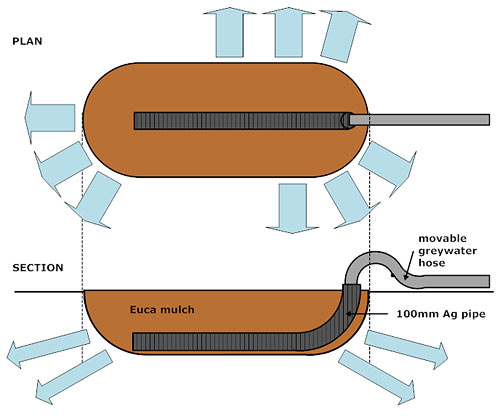

Storm water

and grey water preservation and distribution

by Cam Wilson, Forest Edge

Permaculture

Greywater

mulch-pits provide an excellent solution when

re-using greywater on your garden - they are cheap

to construct, they improve the quality of water

entering your soil and after some time provide you

with valuable compost. They’re very easy to

construct too. You basically just dig a hole, wack

in some 100mm ag-pipe and then fill it up with nice

chunky mulch.

Where

possible a number of pits should be constructed

around the garden. This enables you to rotate your

greywater around and prevent the inevitable

waterlogging that occurs if you leave your hose in

one spot too long. For flat ground it’s great to

create round pits, with each one midway between a

few fruit trees. If on a slope, they will be on

contour and can double as a swale.

The

volume of each pit should be about 4 times the peak

flow that leaves your house at any one time. For

example if your washing machine pumps out 100

litres, the size of the hole needs to be 400litres

(as a guide, 1m3 = 1,000litres). This is to allow

for the space taken up by the woody mulch (about 2/3

of the volume) plus a bit extra. 40 cm is plenty

deep enough, or else you’ll start to send most of

the water down below the main feeder/drinker roots

of your trees.

If

you have very sandy soils in which most water just

disappears straight down, it can pay to line the

inside of your pit with plastic. A few punctured

holes here and there allow you to infiltrate the

water in the direction(s) of your choice. It also

gives the critters more time to clean up the water.

With

the huge increase in the use of greywater on

Australian gardens, particularly here in Victoria

where we’ve been on restrictions for a number of

years now, there is concern about the effect it will

have on soils in the long term. Even if using liquid

detergents, which are much lower in sodium and

phosphorus than powders (see lanfaxlabs for

more info), the alkaline nature of soaps will affect

soil pH. Fats and oils from our bodies can also clog

up soil pores and make them hydrophobic and any

bleaches or harsh cleaners will of course have a

huge impact on soil life.

By

filling these pits with chunky mulch, this acts to

filter and clean the water, resulting in better

quality irrigation for your valuable fruit trees.

It’s not the mulch that does the filtering but

rather the tiny soil critters that will colonise its

surface and just like in a reedbed system, they

greedily grab onto any nutrient that passes by.

Inevitably, this mulch will be broken down into

compost, at which time you should say “Awesome!” and

fork it out of your pit straight onto the fruit

trees beside. Then, give your local tree lopper a

call and get a free/very cheap load of mulch

delivered and refill them. (By the way, this is so

much easier than cleaning out a clogged up reedbed,

plus you get the compost out of it instead of a mess

of aggregate you don’t know what to do with.)

The

simplest way to get water to each pit is by

extending the washing machine outlet hose. You can

rotate this hose once a week or so. A few tips to

prevent your washing machine’s engine from burning

out: 1. Utilise gravity as much as possible; 2. Over

10m+, ensure the extension hose is at least 50mm to

reduce strain on the pump; and 3. Don’t pump uphill

(if you do need to, you’ll have to get a pump built

for this purpose).

If

you include an appropriate length of 100mm ag-pipe

inside each pit, with one end just slightly sticking

out, this means that you can poke your washing

machine hose down inside so that the water

infiltrates sub-surface as regulations rightly

demand (stops kids and pets getting sick from the

pretty nasty pathogens that greywater can contain).

If

you want to utilise your bath and shower water also,

by law you’re supposed to get a plumber in to divert

the water. From here, a more permanent option is to

construct branched drains which evenly distribute

the water around the garden. Detailed design and

installation instructions are available for this

method in Art Ludwig’s book The New Create an

Oasis Using Greywater.

You

can irrigate a 1/8 acre suburban orchard for under

$200, which is pretty good value I reckon compared

to the $10,000-$20,000 approved treatment systems.

When

rainwater harvesting is mentioned, most people think

of tanks straight away. That’s a great start, but

there is a much bigger storage you have available to

you on your land – the soil. (Check out Brad

Lancaster’s fun U-tube video on this site, ‘The muffin tin and the sponge’

for a good intro)

So

when your gutters flow and your tanks are full,

don’t send all that valuable water straight the

drain like so many do. Instead, have a go at

utilising that water in your garden by creating a

system similar to this.

Rural

and semi-rural permaculture systems are often built

with swales incorporated. A swale is

a water harvesting ditch on contour which intercepts

runoff, then fills up and holds onto the water long

enough for it to soak into the soil for the use of

tree crops (You can see plenty of examples of swales

on this website).

Swales

are fantastic, however, in an urban situation not

everyone wants to have a garden that resembles a

motor-cross track, nor gaping wide trenches that

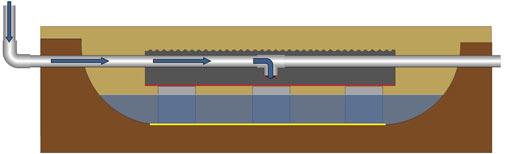

Granny can get lost in. The French-drain design

explained in this article is an alternative, which

has the same benefits of a swale, whilst being

pretty much invisible.

Designing

Just as with swale systems, whenever we are

infiltrating large amounts of water into our soil,

it’s very important to include trees as part of the

design; if not, you risk water logging and quite

possibly salting the landscape.

Don’t

just wack one of these in; you can put a whole

series of them throughout your forest garden for

example. When you’re deciding where they’ll go, it’s

good to be aware that most fruit trees like to drink

and eat at their dripline, so therefore this is

where it makes sense to position your trenches. For

young trees you’ll need to decide where the end

dripline will be and position them there. It’ll take

a while for the young tree’s roots to reach out to

the moisture you’re infiltrating for them, so in the

meantime, you can dig a finger off the side of your

trench to direct water closer to it’s young root

system.

Gravity

is your best friend when playing with water, so

start off by directing your downpipes or tank

overflow to the top corner of your land through some

90mm PVC pipe (even if you think that your land is

flat, there will always be some fall. If not, you’re

either living in the middle of a salt-pan or an

indoor basketball court). From here, work your way

down the hill and position a trench wherever you

have trees and shrubs that can utilise the moisture.

Just make sure that you’re infiltrating water at

least a few metres away from building foundations or

else you can undermine them.

Size and shape

Each trench should be about 50 cm deep. Any more

than that and you’ll be infiltrating the water below

the main feeder and drinker roots of your fruit

trees.

If

your land is relatively flat, you can get quite

creative and make them basically any shape you like.

However, if you are on a slope, you’ll need to make

sure that they are positioned across the slope, that

is, on contour like a swale. Just remember, the

bigger your trenches, the more water it can hold,

and therefore, the more water it can infiltrate.

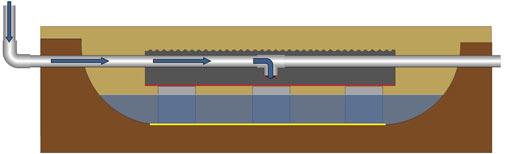

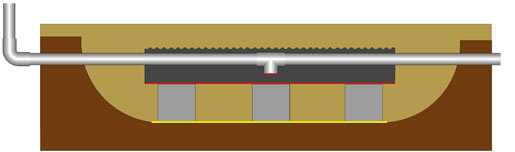

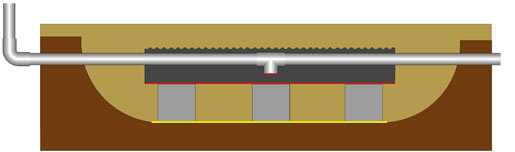

The

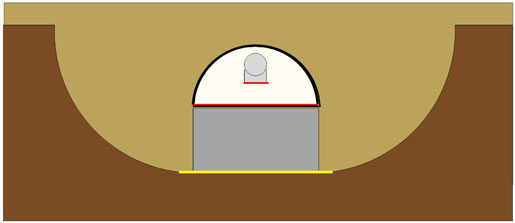

construction is quite simple as the illustration

shows:

90mm PVC pipe.

Begin with some 90mm PVC pipe heading from your

water source with an open 90mm Tee pointing

downwards at the centre of your trench. The top of

this pipe should be about 10 cm below the

surrounding soil level.

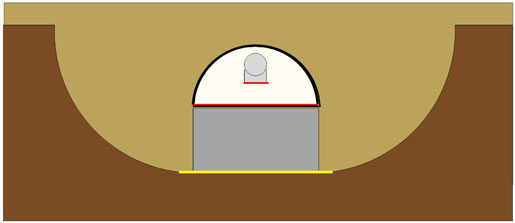

Reln

drain.

Over the top of

the PVC pipe you place an impervious reln drain with

a gap of about 5 cm above the pipe (a reln drain is

a corrugated half-pipe about 40cm in diameter and

comes in 1.5m sections. They’re designed for use in

septic tank leach fields and cost about AUD $15 at

plumbing supply places). The reln drain should be

well supported using old blocks or bricks to prevent

it sinking over time, and to prevent pressure on the

PVC pipe if it’s walked on.

Budgie

wire

(the red line on

the picture). This is placed over the base and ends

of the reln drain and also at the opening of the

tee. This is to prevent the mulch (which the trench

is filled with) from floating up and entering the

pipe.

Old

plastic

(the yellow line

on the picture). This is used to line the base of

the trench, which encourages water to infiltrate

laterally towards the trees’ main drinker roots,

rather than straight down.

Mulch.

The trench should be filled with either coarse mulch

or aggregate. The purpose of the reln drain is to

create an air gap around the pipe, which stops tree

roots from clogging it up (see the front view

below). If you decide on mulch to fill your trench,

it will need to be topped up from time to time, but

will eventually become a lovely big humus sponge. If

you decide on aggregate, you’ll need to line your

trench with Geo-textile matting to stop tree roots

and soil from clogging it up.

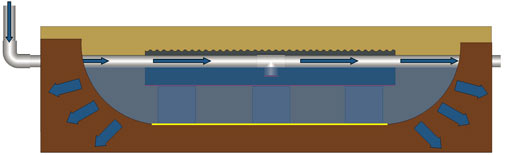

So

basically, what happens is the water flows along the

pipe until it comes to your open tee where it has no

choice but to pour out into your trench.

Once

the trench fills up to the height of the tee, the

water will then continue along the pipe until it

gets to your next trench which it will dutifully

fill etc etc.

On

urban properties, a lot of water can run off all

those hard surfaces during a wetter period or during

a large rain event (A note to Victorians: They will

come again one day, I promise), far more than our

gardens can infiltrate. So it’s really important to

be mindful about the possibility of flooding your

neighbour’s or even your own house.

To

avoid this problem (quite possibly very costly),

once you’ve caught and infiltrated all the water you

can/need, you’ll need to divert it back into the

stormwater drains before it rushes onto

buddy-next-door’s place (by law in Oz, you’ll need a

plumber or landscaper to do this job, but before you

do, have a chat with your neighbour cause he might

like to use the runoff himself).

Similarly,

there will be times when your soil is already as wet

as it needs to be and if you send in much more,

you’ll just end up making your soils anaerobic and

you’ll also leach valuable nutrients from your

system. To avoid this, plumb your system so that

during these wetter times you can just send the

water down the drain.

Good luck and happy

drought-proofing!

Cam Wilson, www.forestedgepermaculture.com

For

methods of collecting water from dew, such as air

wells and dew pods, see

|